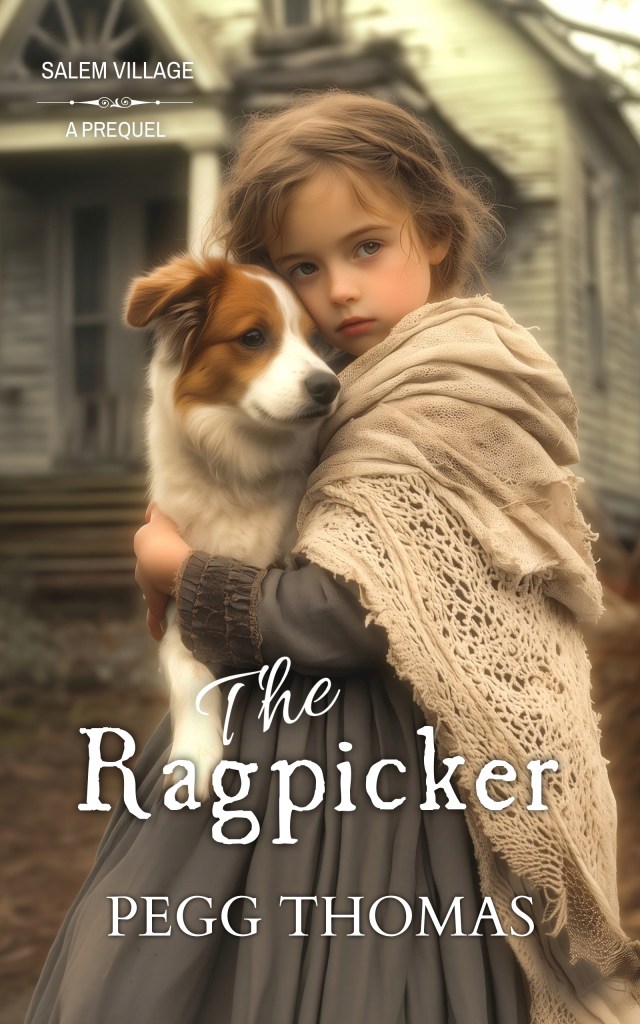

Salem Village – Prequel Novella

In the shadows of Salem Village in 1692, one young girl must navigate the complexities of a divided society.

Often cold and hungry, eight-year-old Verity Manton, an orphaned ragpicker, clings to the scraps of love and kindness in her harsh world. Things get tangled as the village Puritans’ strange behavior grows more alarming. Verity is caught between the safety of her life and the promise of a better future with a Quaker family who reaches out to her. Yet, she has been warned her whole life that Quakers are evil.

Will Verity have the courage to trust her heart and choose a path that defies everything she has been taught? This powerful prequel novella to the Salem Village series will leave you on the edge of your seat until the very end.

Tropes: Crisis of Faith – Unlikely Allies – Quakers – Cost of Conviction – Hidden Secrets – Faith vs Culture – Hard Choices – Salem Witch Trials – Orphan Girl

Chapter 1

November, 1691

Uncle William was dead.

Like Momma and Papa had gotten dead three years before, although Verity Manton could barely remember them. They were shadowy figures who sometimes visited her in her dreams, along with her baby brother and sister. She didn’t like those dreams because she awoke crying and sweating and fearing Indians.

But Indians hadn’t killed Uncle William. He’d just withered away, even though he’d not been an old man. The doctor called it yellow fever, but to Verity, it had more to do with the vomiting and flux than the yellow tinge to her uncle’s skin. A person could live with yellow skin, but not if he couldn’t keep anything inside.

She might be only eight years old, but she knew that to be true. No matter how hard she’d tried, what broths she’d made or what teas she’d brewed, he’d lost everything she’d spooned into him.

Verity had done her best, but it hadn’t been good enough.

Men shoveled dirt into the long hole holding the plain wooden coffin as rusty leaves swirled around the opening. The sheriff’s wife, Goodie Corwin, held Verity’s hand. Just the two of them watched, and Verity only knew Goodie Corwin from seeing her in church. There were no other mourners, not that Uncle William hadn’t been a good friend and neighbor. People stayed away because they feared the fever.

Dirt thudded on the lid of the coffin until it was covered. Uncle William hadn’t been afraid of the dark, unlike Verity. He’d often comforted her when the bad dreams came, never lighting a candle, just holding her and telling her that God loved her.

She’d never hear his voice again. A shudder passed over Verity, but no tears came. She’d cried so many already, maybe they were all gone.

Goodie Corwin’s hand tightened around hers. The kind lady stayed beside her until the last shovelful of dirt had been patted into place, sealing Uncle William away forever. Then she knelt to Verity’s level.

“There is a woman coming to claim you.” Goodie Corwin had a kindly face and gentle eyes, but the line of her mouth said she didn’t like what she was saying. “I fear we could not locate a relative, but Widow Scudder has taken in many orphans before, I am told. She will give you a home.”

Verity pulled her hand away and crossed her arms. “I do not know her.” Oh, why did Uncle William have to die? She didn’t want to be alone, but she didn’t want to go with a stranger either.

Goodie Corwin touched her shoulder. “She lives in Salem Village. ’Tis a lovely place, mostly farms, and they have their own church now with a proper Puritan preacher installed, a Mr. Samuel Parris.” She mustered a smile. “He has a daughter very near your age. Perhaps you will find a friend in her.”

A friend? Like Patience before… before the Indians. But Patience and her family were buried near Momma and Papa. “What is her name?”

“I have not had the pleasure of meeting her, but I am sure introductions will be made at services on Sunday.”

The girls in Salem Town had not taken to Verity, an outsider from the wilds of Maine who lived with a bachelor uncle. At first, grief and fear had kept her clinging to Uncle William, even during services, although it was most unusual for a girl her age to be so clingy. The adults had been tolerant of her emotional distress.

The children had only seen her as different—in a society where conformity was a virtue.

And when the dresses Momma had made grew too small, Uncle William had bought hand-me-downs from the most gossipy woman in the church, whose five daughters had tormented Verity about it. It’d been easier to stay in the house and work at the tasks she knew, tasks Momma had taught her before the Indians, like sweeping and scrubbing and washing clothes. Uncle William had praised her on what a fine job she’d done on his shirts.

Tears blurred the face of the woman in front of her, so they weren’t all dried up yet. “I would like a friend.”

“I know.” Understanding filled Goodie Corwin’s voice. “’Tis why I agreed that Salem Village would be a good change for you.” She smoothed Verity’s wayward hair back under her bonnet.

“Is this the girl, then?” A scratchy voice interrupted them.

Goodie Corwin straightened, keeping one hand on Verity’s shoulder while looking over her head. “Are you Widow Scudder?” Her words were something between a demand and dismay.

Verity turned, dread climbing her throat like a squirrel up a tree.

“’Tis my name.” The woman was older than anyone Verity knew. Her hair was covered with a scrap of cloth tied beneath her chin, not a proper bonnet, and her face held more wrinkles than a spring apple. Her dark eyes were almost lost in the folds, and when she spoke, no teeth graced the puckered opening of her mouth. “Is this the girl I am to take away?”

“I was led to understand that you took in orphans.” Goodie Corwin’s fingers tightened on Verity’s shoulders. “I assumed you to be a younger woman who—”

“’Tis the older who need help, not the younger.” The old woman sized Verity up with a sharp glance. “She will do. Come, girl.” She extended a gnarled hand.

Verity shrank back against Goodie Corwin.

“Ah, Widow Scudder, I see you have come on time.” Sheriff George Corwin, one of the men who’d buried Uncle William, approached, carrying the sack of Verity’s belongings they’d left near the grave. He cast an uneasy glance at his wife. “Is anything amiss?”

“’Tis only that I had a different idea about who would—”

“And I told her, I have need of the help.” The widow thrust out her hand again. “Come, girl. ’Tis a long walk back to Salem Village.”

The Sheriff handed Verity’s sack to the old woman. “I am sure everything will be fine. Widow Scudder knows what a child needs. She has years of experience with them.”

“That I do.” The old woman opened the sack and peered inside.

It contained everything Verity owned, and she wanted to snatch it back, but she couldn’t move. Her body was numb. Her mind was angry, which she knew to be a sin, and sinning was wrong. So she welcomed the numbness.

“Come, my dear.” The sheriff held out his hand to his wife while bowing to Widow Scudder. “If you will excuse us, we must be on our way. Good day to you.” He eased his wife away.

Goodie Corwin gave Verity’s shoulder one last squeeze, a pressure that echoed in Verity’s throat. “All will be well,” she said as her husband led her away with hasty steps.

Verity wanted to run after them. Even though she barely knew them, they were her last link to Uncle William. But the numbness wouldn’t let her.

Widow Scudder grabbed her arm in a pinching grip. “Come on, girl.” She slung Verity’s sack onto her back. “You belong to me now. Do as you are told, and we shall get on fine.”

The Corwins were already out of sight on the other side of the church.

The cross from the steeple painted a dark shadow on the grounds of the churchyard, pointing to Uncle William’s grave. Verity wanted to go back and say goodbye one last time, but Widow Scudder set off in the other direction.

There was no one left for her in Salem Town and nothing for her to do but take one numb step at a time after the old woman, who didn’t release her arm.

***

The sun hung low in the west and slanted shadows across the dirt street of Salem Village. It was nothing like Salem Town. For one thing, Verity couldn’t smell the ocean. It smelled more of forest and fields, like her old home in Maine.

Grief welled over her even as she followed Widow Scudder. She pulled her tattered shawl—Momma’s old shawl—tighter across her shoulders. She missed Momma and Papa and Uncle William so much, it hurt in the center of her chest. And the tears she’d thought were dried up had dribbled down her cheeks several times during the walk to the village.

Her feet were sore. The numbness had worn off, and her too-tight shoes were pressing against her toes. She needed a larger pair. Uncle William had said he’d buy her a new pair for winter, but then he’d gotten sick. And died.

The widow hadn’t said a word to her for the entire journey, but she’d released her grip on Verity’s arm early on. Verity had no trouble keeping up with the old woman, whose steps shuffled in the colorful leaves.

The village was a collection of whitewashed buildings, including a church with its steeple pointed heavenward and businesses with painted boards out front swinging from ropes or chains. Verity couldn’t read, but most had pictures to show what they were. And the blacksmith shop had open double doors. The heat and light from its forge spilled into the street, its acrid scent lending a sting to the air. They passed house after house, at least two dozen of them, most made of milled boards with porches and steps out front. Some were only log structures that again reminded Verity of Maine.

Widow Scudder didn’t slow or even look around. The old woman’s mouth drew a puckered line, and Verity was afraid to ask where they were going as the houses receded behind them. It didn’t really matter. She had nowhere else to go.

In the distance, at the edge of the forest, long past the last house on the street, squatted a dark shack. Or maybe it was dark because the shadow from the forest covered it, the sun sinking below the treetops. Widow Scudder’s steps, slow though they were, never wavered.

Verity’s heart sank. It would be dark in that shack. There was only one window on the front, a very small one, and no light glowed from inside. The even darker forest lurked behind it. Did Indians live there?

“Where are they?”

Verity startled at the scratchy voice beside her.

“Jumpy little thing, you are.” The wrinkle-rimmed eyes skimmed over Verity again. “But I suppose you got reason enough. I am sorry your uncle died, child.”

Words wouldn’t squeeze past the tightness of Verity’s throat, but she managed a nod.

“You behave, do as you are told, and all will be well.” The old woman snorted. “But I suppose you will run off and find mischief for yourself like the rest of them.”

Working up all her courage, Verity cleared her throat. “Who?”

Widow Scudder waved a hand at the forest shrouded in darkness. “The other orphans who live with me and work for me, as those who did before.”

“There are others?” A small gleam of hope crept into Verity. She wouldn’t be alone with the old woman.

“Two at the moment, but the Lord only knows where they have gotten themselves off to.”

Verity never wanted to be the reason the widow’s voice took on that ominous tone, nor to cause the old woman’s mouth to crease into its fearsome scowl.

They reached the shack, which the widow called a cottage, and it was as dark as it’d looked from the distance, lacking any sort of whitewash. Lacking a porch, the building seemed to settle directly onto the forest floor. The widow pushed open the door that hung from leather hinges, and Verity stepped inside onto a packed dirt floor.

With the door shut behind them, the feeble light from the only window cast an eerie shaft across the single room’s sparse contents. A wattle-and-daub hearth took up most of one wall but held no welcoming flame or heat. Against the opposite wall, a narrow bed sagged under a tatty brown blanket. The back wall held four wide shelves stacked in pairs, with more blankets wadded on top of them. A square table stood in the middle of the room, with benches along two sides. One chair sat near the hearth. A handful of large baskets hung from the rafters, along with bundles of herbs, ears of dried corn, braids of onions, dried fish, and strings of dried green beans. The building smelled of dirt and fish and old things.

“Light a fire, girl.” Widow Scudder pointed to a box half full of wood.

Verity knelt beside the hearth, knees pressed into the soot and dirt, and stirred the gray ashes until she uncovered a dull ember. She leaned over and blew on it until it glowed, then added small bits of bark until it caught. She added slivers of wood until a little blaze was going.

“Someone taught you well enough.” The widow’s voice still crackled, but there was a faint undertone of approval.

“Momma did.”

The old woman sat on the chair with a thump and a heavy sigh. “What is your name, child?”

“Verity Manton.”

“Pretty name.” The dark eyes gleamed in the fire’s light as she examined Verity again. “How old are you?”

“Eight years old this past August.”

“Mmm-hmm.” The old woman rubbed her chin. “You are a pretty one. That never hurts when asking for scraps.”

“Scraps?” Did the widow expect her to beg for food? Uncle William had given to the poor who sometimes came to the house, so she’d seen beggars. Verity wasn’t a beggar.

“Aye, child. We all have to work together here if we wish to eat.”

Verity was used to working in the house. Momma had needed her help after her brother and then her sister were born, and especially after her brother had died of illness. Momma had suffered from melancholia for many weeks after his death. Papa had been so worried.

Then the Indians came, and Verity only survived because she’d been sent to the fort for a bag of salt to brine pickles. If she’d been home, she’d be in the churchyard in Maine with her family. Instead, she’d gone to live with Uncle William and keep house for him.

If only she’d died with her family, she wouldn’t be in a gloomy shack in Massachusetts with a frightful old woman she didn’t know.

“You will be our ragpicker, little Verity.” The old woman nodded as if satisfied with her announcement.

Verity shook her head. “I cannot be a ragpicker.”

“Whyever not?”

“Only the very poor and the infirm are ragpickers.”

“Child.” The old woman spread her arms as if to show off the shack’s single room. “You are very poor now. ’Tis time to get used to that idea. We all work or we do not survive. You will beg for scraps of cloth, food if anyone will give it, and scavenge where you can. Becky will unravel the rags for their threads, cook, and keep house. You and she can untwist the threads in the evenings. Joseph will keep the woodbox filled, fish in the stream, tend traps for meat, and make the journey to Salem Town to sell the untwisted fibers to the papermaker there.”

Verity’s knees trembled as she rose. “From whom will I beg?”

“The townswomen, the local farmers, the merchants—it matters not. There is a dump on the town’s eastern edge to scavenge from as well.” She shook a gnarled finger at Verity. “But you stay away from the Quakers, girl. Those people are the devil’s own, you hear me?”

Verity nodded. After all, she’d always heard it was best to avoid them. Everyone knew they were sinners on their way to hell for their ungodly ways.

The old woman held her hands out to the flames, then rubbed them together. “You must learn quickly. Winter is almost upon us.”

The meager supplies hanging from the rafters would not be enough to feed a single person through the cold months, much less four.

The door opened, and a gust of cold air rushed in. A girl entered, older than Verity, but not yet on the edge of womanhood. She had long dark hair pulled back and covered with a cloth much like the widow’s. Her eyes were dark as the night, and her skin pale enough to give her an almost spectral appearance. She removed the head covering and glared at Verity.

Behind her came a boy with a thatch of uncovered hair the color of straw. Upon seeing Verity standing by the hearth, his wide grin exposed bright teeth and a dimple on each tanned cheek. The two couldn’t have looked more opposite of each other, although both were thin to the point of skinny and wearing clothing long past its prime.

“Becky, Joseph.” Widow Scudder pointed at each as she said their names, then to Verity. “This is Verity—our new ragpicker.”

The shame of that title settled on her narrow shoulders like a weight of condemnation. What would Uncle William have thought? Or Momma and Papa? She’d tried so hard to be good, but it hadn’t been enough. And now she was to be nothing more than a beggar.

paperback ISBN: 979-8-9929079-1-9 – ebook ISBN: 979-8-9929079-0-2 – audiobook ASIN: B0F8GV66RZ

Return to https://peggthomas.com/