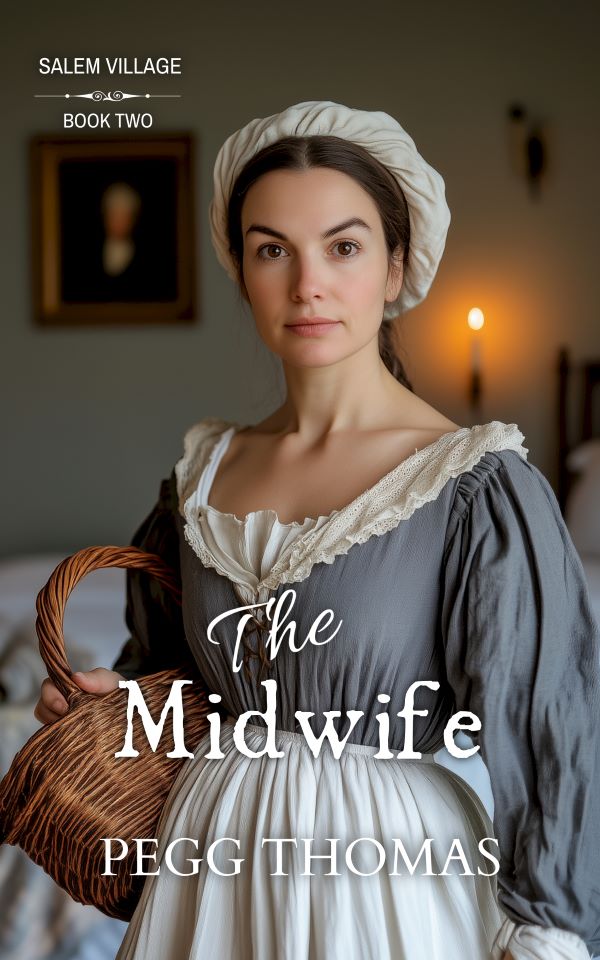

Salem Village – Book 2

Amid the infamous Salem Witch Trials, two single women must navigate their own personal struggles while staying true to their beliefs and those who depend on them.

Hester Fuller, a Quaker midwife, is determined to maintain her home and provide safe childbirth for the women of Salem Village. But when a mysterious basket appears on her doorstep, Hester’s fate hangs in the balance.

Meanwhile, Hannah Buffum, Jr., a Quaker woman, finds herself drawn to the Puritan Benjamin Buffington, despite their opposing beliefs. As their attraction grows, Hannah must grapple with staying true to her family and faith while also working together with Benjamin’s family to help those in need.

Tropes: Crisis of Faith – Unlikely Allies – Quakers – Cost of Conviction – Hidden Secrets – Faith vs Culture – Hard Choices – Salem Witch Trials – Midwife – Orphan Baby

Chapter 1

April 1

“’Tis a false alarm, but thy aunt was right to fetch me.” Hester Fuller patted the back of Jane Biddle’s hand. “There may be a few of them before the day is to come. I should think the babe will remain where it is for at least another fortnight.”

The brown-haired woman on the bed gave her a weary smile. “I told my aunt ’twas too soon, but she worries so.”

As well she should, but Hester wasn’t about to admit it and upset the mother-to-be. This was Jane’s fourth child, and as such, should have been less complicated. But she’d become pregnant on the heels of her last babe, a little girl who had turned a year old last week. She’d not given herself proper time to rest in between. Hester firmly believed that two or three years between births was best for both the mother and the infant.

The aunt, Sarah Cloyce, sat on a chair on the other side of Jane’s bed. “I am sorry for bringing you out for no cause.”

“’Tis no bother.” It never failed to amaze Hester that a woman could give birth—nine times in Sarah’s case—and fail to remember the details of the experience. Once the babe was in her arms, all thought of the process seemed to slip away. Perhaps it was God’s blessing. “Do not hesitate to call me back if thee are unsure. A fourth child can make a surprisingly fast appearance.”

Sarah sighed. “I remember my fourth. Such a winsome child.”

“I should be on my way.” Hester lifted her basket and strode to the door before Sarah could launch into her memories of all nine of her birthings. “Do not hesitate to fetch me again. ’Tis only a short walk down the street.” She slipped out the door and down the stairs.

“Midwife?” Jane’s husband stopped his pacing in the parlor as Hester entered.

“’Twas a false alarm.”

The air seemed to melt out of the tall man. Thin to the point of skinny, he bent forward, hand to his forehead, the faint light of morning filtering through the window behind him, dimming the light of the single lit candle on the side table. “Does it never get easier?”

Hester refrained from chuckling. Husbands came in two varieties, it seemed, those who suffered along with their wives, albeit from a distance, and those who regarded childbirth a woman’s responsibility, and therefore of little concern to themselves. Hester much preferred John Biddle’s sort. It was her high success rate for assisting with live births—something she took pains not to be proud of—that made her popular with her Puritan neighbors, but any birth had its inherent dangers. It did the man credit that he cared so much for the woman upstairs and their unborn child.

“Each babe will come into the world in his or her own way, some easier than others.” Even though Hester had never given birth herself, she’d assisted well over a hundred women between helping her physician father, and then becoming a midwife after the death of her intended. That had caused a bit of a stir, even among the Friends, to have an unmarried woman as midwife. But there had been few options at the time, and her training had been exemplary. It hadn’t taken long before she was accepted by both Friends and Puritans alike.

She wished John Biddle a good day, and then stepped out into the fresh air of an early April morning. Smoke drifted from the chimneys in town, hanging low with the promise of rain to come. Sweet April showers, doth spring May flowers. The old poem, as appropriate that morning as when Thomas Tusser had penned it some hundred years past, was one of her favorites.

If only the village were as peaceful as it seemed. If only a good spring rain could wash away the taint that hung over it.

Hester was the only Friend living within the village limits, which had a statute that restricted property ownership to members of the Puritan church. She rented a humble cottage from the innkeeper, Nathaniel Ingersoll, and the village elders permitted it because their women wanted a midwife they could count on nearby. Even though they had a new, rather elderly, physician in town, the women were generally more comfortable with a woman assisting in childbirth.

Which had suited Hester just fine until the accusations of witchcraft had begun.

Everyone knew that the first execution of a witch in the American colonies had been Margaret Jones, a midwife, back in ’48. A shiver crept up Hester’s back. Margaret Jones had been a Puritan among Puritans. How much more vulnerable was Hester as a Friend living among Puritans? Several of the families among their Friends had offered her a place in their homes, but she’d resisted. Partly because she enjoyed her independence, and partly because she feared that the Puritan women—or their husbands—wouldn’t fetch her from a Friend’s farm when their time came. As accepting as they were of her, that might be too much for them. They were a stiff-necked lot, even if, taken one at a time, most were agreeable to be around.

She reached her cottage and entered through the back door, wiping her feet on a colorful rug one of the Puritan ladies had gifted to her after the birth of her child. None of the Friends would have created something so vibrant, preferring the somber, plain hues of soft grays, blues, browns, and greens. But it made Hester smile when it greeted her upon her return, and so she’d kept it.

Pushing aside the makings of another basket, Hester put her midwife’s basket on the table. She stretched and yawned. No sense in going back to bed, as morning was already breaking. She’d mix herself a bit of porridge and then hunt in the forest for more basket-making materials. Spring was a good time to gather red-twig dogwood shoots, river willow withies, and woodbine vines. Selling her baskets in the village and in Salem Town, along with her midwife fees, allowed her to stay in the cottage. The income supplied the independence she enjoyed.

Perhaps a little too much.

The alternative was to live as a spinster aunt with one of her brothers, which she did not favor. Her sister would take her in, of course, but Emily lived in Connecticut Colony, so far away. Hester had turned down the matrimonial offers of several widowers with children in need of a mother. Not that she didn’t love children, she did, but to be married to a man other than Timothy Newman? That she couldn’t do. There’d only been one Timothy, and God had called him home far too soon. Far too young.

Perhaps it was knowing she’d never have children of her own that made Hester so passionate about the babes and mothers she assisted. Timothy’s death had changed everything for her, and perhaps for those children she’d successfully ushered into the world. It was good to think that God was working out His plan, that Timothy’s death had been just a senseless farming accident.

***

It was still early enough in the year to let the cream rise in the cool of the dairy. Hannah Buffum, Jr., poured fresh milk into wooden troughs on her workbench. In another week or two, she’d need to haul the buckets to the spring house to keep the milk cool from the fresh water that flowed through the trough Father had built there. With the cows out on pasture and grazing the early greens, their milk was thick and rich with cream. It was the best time of year to make her hard cheeses, which needed to cure for several months.

Hannah Jr. enjoyed the process of cheesemaking. It gave her a purpose beyond helping her mother with the house and the children. The eldest of originally six children—now eight counting the two orphans currently living with them—she split her time between the dairy and the house. She was also training her sister Tamson to work in the dairy, along with Verity, the orphan who had been given into their family by the Puritan elder, Thomas Buffington, just the past week. Hannah Jr. couldn’t help but be happy at the thought of having another sister in a family so full of brothers.

The door separating the dairy from the main part of the barn banged open. Joseph, the boy living with them until the situation in the village changed, poked his head inside, straw-colored hair disheveled and gap-toothed grin wide. “Old Buttercup is calving right now. Come and see.” He disappeared as suddenly as he’d arrived.

The boy had been going on and on about witnessing a cow give birth for the first time. Hannah Jr. and her siblings were used to the rhythm of farm life—birth and death, planting and harvest. They took everything in its season. But to Joseph, a boy orphaned very young and shuffled from one house to another, it was all new. And very exciting.

Since the cream would rise without her watching it, Hannah Jr. slipped off her dairy apron and hung it on its peg before following the lad through the barn, past the area that still smelled faintly of smoke from the fire last winter, and on to the cows’ pen. Buttercup, their poorly named cantankerous cow, let out a raucous bellow as they approached. She was alone, the other cows having gone outside to graze after milking.

Robert and Caleb Jr. were already watching. Nobody would approach Buttercup unless they had to. While some of their cows were docile and allowed themselves to be handled even in labor, old Buttercup was against any human interference in the birthing process. Strenuously against it. Once, she’d even tossed Father over the top rail of the cow pen.

Another long and loud bellow brought Father out of his carpentry shop. He rested his forearms on the top of the gate. He wore just his waistcoat in such fine weather, curls of wood from his current project clinging to his shirtsleeves. He was working hard to finish the large order for the new doctor in the village.

Hannah Jr. stifled the sensation in her middle at the thought of that order. Not the order, exactly, but the man who might come to collect it for the doctor—Benjamin Buffington. She shouldn’t be thinking of him at all, but she couldn’t help it. He was the only young man who had caught her eye. Three years her junior, he was two years from majority age, but that wasn’t the real issue.

Benjamin was a Puritan.

The Society of Friends didn’t intermarry with Puritans, and the Puritans would reject the possibility even more forcibly. The last thing Hannah Jr. needed was to replay some tragic version of Romeo and Juliet. She shouldn’t even have known about that play of William Shakespeare’s, but her friend Mary O’Sullivan had somehow gotten a copy of it and had shared it with Hannah Jr. Guilt still pinched her over reading such a worldly story, and that’d been several years past, when she’d been a youth.

Buttercup gave a mighty push, and the tips of the calf’s front hooves poked out, and then disappeared again.

“I do not favor the look of that,” Father said.

Tamson and Verity arrived with the little boys, Benji and Jonathan. “Why, Father?” Tamson, Hannah Jr.’s twelve-year-old sister, climbed onto the gate until her head was level with Father’s.

“Because there was no nose showing with the hooves.” It was Caleb Jr. who answered. At eighteen years old, he was the eldest of the brothers and four years younger than Hannah Jr., who answered.

“Is that bad?” Joseph’s brow wrinkled.

Father put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. “It can be. We shall have to wait and see.”

“Will she die?” Tenderhearted, nine-year-old Verity had never witnessed a cow giving birth either.

“Death is as much a part of life as birth is.” Hannah Jr. drew the girl to her side. “’Tis one of the things we learn early on the farm.”

“I know about death.” Verity’s arms came around Hannah Jr.’s waist. “But I wanted to see a birth.”

The words hit Hannah Jr. hard. This child had suffered so much loss. Was it too much to ask that she be able to witness a happy occasion in the barn?

Buttercup sank to her knees, then groaned and rolled onto her side, her tail cocked as she heaved against another contraction. The hooves appeared again, even further this time—but still no nose.

Father rolled his sleeve up well past his elbow and took a stout piece of tree limb with a curve to it from its storage place near the pen. Caleb Jr. fetched a length of rope. Robert ran for a bucket of water. Hannah Jr. and Tamson kept the young boys out of the way. They’d all done this before, more than once.

Not always successfully.

“What is happening?” Joseph asked.

“They must assist Buttercup. ’Tis most likely that the calf’s head is turned back.”

“What will they do?” There was a tremor in Verity’s voice.

Hannah Jr. squatted to her level. “They must turn the calf’s head around so that it can come out of Buttercup.”

Jonathan started to whimper, so Hannah Jr. scooped him into her arms. At just three, he hadn’t seen this happen before either. Most birthings occurred in the barn or out on pasture without any assistance.

Father and Caleb Jr. entered the pen first, the limb held between them. They waited for Buttercup to give another mighty push, then rushed forward, pressing the limb against her neck, right behind her ears, pinning her to the barn floor. Robert left the bucket of water near her tail, then took Father’s place holding one end of the limb.

Buttercup bellowed and kicked, but the boys and Father knew how to stay out of harm’s way. Father wetted his arm, waited until after the next push, then grabbed the hooves with the rope in his hand. When the hooves disappeared again, Father’s hand, arm, and the rope went with them.

Verity turned her face into Hannah Jr.’s petticoats, while Joseph let out a loud, “Ugh.”

Robert, almost sitting on his end of the limb near her back, spoke in a soothing tone to Buttercup.

Caleb Jr. kept both hands on his end, being careful not to cut off the cow’s breathing by keeping the limb’s curve up as he knelt near her throat. He was doing a good job of it, judging by the increased volume of her bellowing.

The straw around Father’s feet was mussed as he strained to reach the calf’s head, groaning against the cow’s next contraction. “I have the rope in its mouth.” The words came through gritted teeth. “Now to get it around the bottom jaw.”

Verity peeked from Hannah Jr.’s petticoats while still clinging to them.

Joseph had climbed to the top rail of the pen, where he sat open-mouthed.

Father groaned again as Buttercup bore down, but as soon as she ended the push, he dug his toes in and pushed back almost to his shoulder, his other hand keeping the rope taut. “’Tis turned.” Father pulled his arm out. It was covered in slime and blood enough to make Verity blanch. He got to his feet. “Let her up, boys, and get out of here.”

Caleb Jr. and Robert dropped the limb and ran for the gate, Father not a full step behind.

Buttercup lurched to her feet with the closest thing to a roar that a cow could manage and turned to face them, the calf’s front legs and nose swinging out behind her.

Father got the gate shut and the latch thrown across a breath before the cow smacked into it.

The cow’s anger reverberated on the pen’s boards, and Joseph teetered, nearly losing his balance.

Caleb Jr. grabbed him before he tumbled into the pen with the irate bovine.

After another smack against the gate, Buttercup returned to the far side of the pen and bellowed, nose in the air. Behind her, the wet calf slid onto the straw with a frightful thud.

Hannah Jr. held her breath until the calf raised its head and shook, wet ears slapping against its neck.

“Look at that!” Joseph pointed.

Buttercup ignored her babe and charged the bucket in the middle of the pen, driving her head into it. The sharp crack of sturdy oak seeming to satisfy her. She returned to the calf, muttering to it as she licked it dry.

The calf shook its head again, mouth opening and closing as it spat out the loop of rope that had guided its nose around.

“Ungrateful old beast.” Chuckling, Father dried off his arm on a piece of sacking. “If she did not produce such fine milking heifers…” He let his threat remain unspoken.

“Will the calf be all right?” Verity asked.

Robert answered, “It should be right as raindrops now.” Even as he spoke, the calf struggled to rise.

“She did it again.” Father rested his forearms on the top rail. “Another heifer.”

“May I name her?” Verity asked.

Father smiled at her. “And what would thee name her?”

Verity clasped her hands beneath her chin. “Buttercup Jr.”

The boys groaned, but Father nodded his approval, so Buttercup Jr. it was, and the rule was, a named calf stayed on the farm.

Which meant another good milk producer for their herd. Hannah Jr. set Jonathan down and picked Verity up, giving her a squeeze and enjoying the girl’s squeal of delight. The live calf meant so much to her, who had lost so many. Hannah Jr. had never suffered as Verity had. She’d never gone without her needs met by her parents, had never lost anyone she was close to.

What right had she to pine over some young man who was beyond her reach?

It was time to put thoughts of Benjamin Buffington aside, and concentrate on being the best dairymaid she could be. The best daughter and big sister too. She who had known only blessings needed to concentrate on being a blessing to others. That was a noble life for anyone, and honoring to God.

The empty feeling in her middle would surely lessen with time.

paperback ISBN: 979-8-9929079-5-7 – ebook ISBN: 979-8-9929079-4-0

Return to https://peggthomas.com/