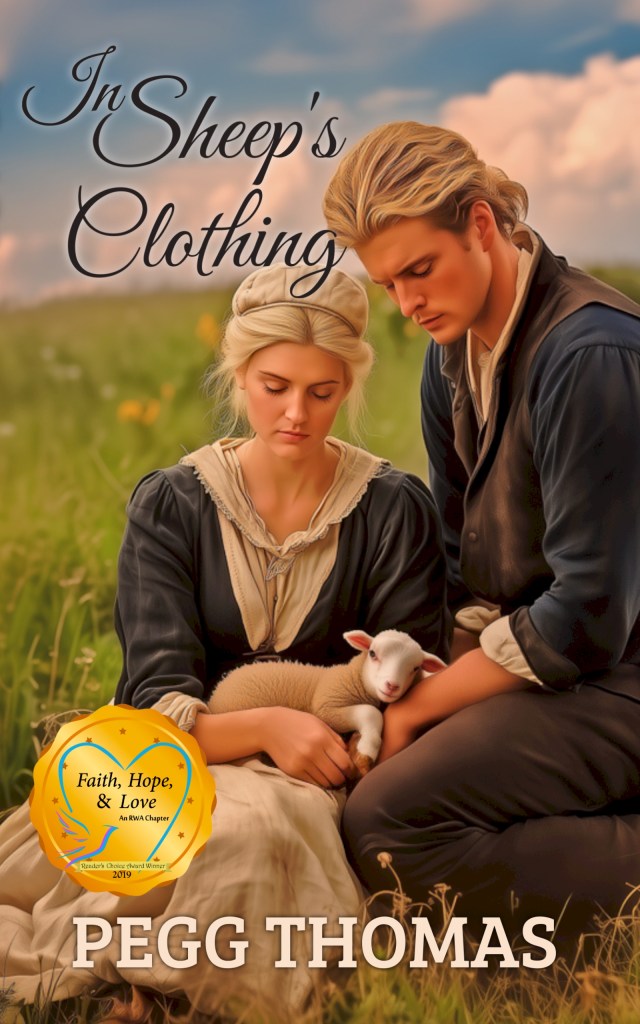

a novella

Originally published in A Bouquet of Brides Romance Collection

2019 Winner of the Faith, Hope, & Love Readers Choice Award

Yarrow Fenn, the talented spinster sister, was passed over when her intended walked out on her years before. She’s content with her life – for the most part – until Peter Maltby arrives in town.

A journeyman fuller Peter Maltby comes to Milford, Connecticut, not to woo the young women, but to rise to the rank of master fuller and return to Boston for some unfinished business.

When their lives intersect over an orphan lamb, sparks are kindled. But their budding romance will have to survive revealed secrets when someone else shows up in Milford.

Tropes: Reluctant Hero – Slow-Burn Romance – Crisis of Faith – Wounded Hero – Strong by Vulnerable Heroine – Spinster

Chapter 1

With a final snip, another layer of guilt fell into Yarrow Fenn’s lap. It landed amid the soft folds of wool from her loom. This cloth was quite possibly the best she’d ever made. She ran her fingers over the loosely woven threads. Once finished at the fulling mill, it would make a splendid gown. But not for her. The guilt pressed against her chest, tightening her shoulders. The traveling peddler would buy this bolt of cloth when he arrived in a few weeks. He’d sell it in Boston—in direct conflict with the king’s law.

She cast a glance out the window, the sun already well above the horizon. Pushing aside the guilt, she folded her cloth into a flat bolt. After several futile attempts to tame her wayward hair under its linen cap, she pinned her straw hat over the top and slipped on her shawl before gathering the newly woven cloth into her arms.

Her room on the back of the saltbox-style house had its own entrance. She nudged the door shut behind her with her foot then hurried around the front of the house. She was neither quick nor quiet enough.

“Where are you going?” Pennyroyal, Yarrow’s younger sister, stood in the front doorway with her hands on her eighteen-year-old hips, her belly straining against the pleats of her apron.

“’Tis the opening day of Tucker’s Fulling Mill.” That Penny could forget the main topic of conversation after church yesterday, the opening of the mill and the impending arrival of the new journeyman fuller, testified to her preoccupation with the coming babe.

“I had quite forgotten.” Penny pressed the back of her wrist to her forehead. “Hurry back. I feel poorly again today. You shall need to start supper.” She shut the door.

Pray the babe would come soon. Penny, ever the spoiled youngest of the three sisters, had bordered on tyrannical these past few weeks. But one must make allowances at a time like this. Yarrow shrugged and walked on.

Their house rested on the northern edge of Milford. Yarrow followed the road toward town. When she turned onto the main road, the steeply pitched roof of the new fulling mill on Beaver Creek was just visible. Excitement bubbled and eclipsed, for the moment, her guilt.

When King William III had signed the Wool Act of 1699, the result had been a financial blow to the citizens of Milford. The act’s restrictions on selling any wool or wool product outside of their colony had put the old fulling mill out of business. That left the weavers of Milford the difficult task of hand-fulling their own cloth to achieve the necessary tightening and brushing of a finished fabric.

Yarrow was relieved to have that back-breaking chore off her shoulders. The line queued outside Tucker’s Fulling Mill said she wasn’t alone, and that boded well for the business. She took her place behind a knot of young women and caught part of their conversation.

“Ginny’s mama saw him come off the boat last evening. She said she fairly swooned when he removed his hat and bowed to Mrs. Tucker.”

“Is it true he does not wear a wig but grows out his own hair?”

“I heard ’tis the color of spun gold.”

“Mr. Tucker told my papa that Mr. Maltby was the youngest journeyman fuller in all of Massachusetts Colony.”

“They say he is not but two and twenty.”

“He must be ever so talented.”

“And tall, they say.”

“And single.”

The cluster heaved a collective sigh. One of them gave Yarrow a polite smile before turning back to her group. Yarrow pushed down a prick of irritation. She knew the exclusion wasn’t intended to slight her. It would never occur to them to include her in their excited chatter about the new journeyman fuller. At the advanced age of four and twenty, all of Milford recognized her as a spinster. Likely all of Connecticut Colony.

Movement near its door signaled that Tucker’s Fulling Mill was open for business. A tall man with golden hair stepped to a trestle table erected outside the door. He must be Mr. Peter Maltby, whose name had dominated the conversation after church. A ripple of excitement slid down the line. Any newcomer to the area drew attention, but a tradesman who eschewed the customary wig was something to set the town’s tongues wagging. Being young and single, he set them on fire.

Tamping down any interest in the man himself, she watched as those in front of her presented their bolts of cloth for finishing. Yarrow was recognized as one of the best spinners and weavers in the colony. As a lad back in England, Papa had been apprenticed to a weaver, and she’d learned at her papa’s knee. Yet it wasn’t vanity, at least not entirely, that caused her to stroke the fabric in her hands. If she could sell three full bolts to the peddler when he came to town twice a year, instead of the usual single bolt left over after meeting the needs of her sisters’ growing families, she might put aside enough to one day purchase a small cabin of her own, scandalous as that may be for an unmarried woman.

The guilt tweaked again. The penalty for breaking the king’s law was severe, perhaps even death. Yarrow didn’t actually sell her fabric outside of the colony. She sold it to Enos Watkins, the traveling peddler. He was free to sell it in the next town down the road. Except she knew he didn’t. Quality cloth such as hers fetched a much higher price in Boston. Knowing he was selling her cloth across the colony’s border made her uneasy, but Enos would never betray her as the source. He owed her for far worse. But she knew what the church would say if they were caught.

The line crept along. Mr. Maltby took his time with each person, asking questions and jotting notes on slips of paper he tagged on the bolts. He was either very thorough or enjoying the batted eyes, practiced smiles, and soft laughter muffled behind dainty fingers. Most men doubtless enjoyed such attention.

Yarrow looked away, some of the sparkle erased from her morning. Most days she was happy enough with her life. Glancing back at those golden locks bent over another bolt of cloth, she sighed. Today was not one of those days.

***

Peter placed another lumpy bolt of woven fabric on the pile. He was supposed to miraculously turn it into a usable household textile. Mr. Tucker had warned him that the cloth-making skills of Milford might not be up to the standard he was accustomed to in Boston, but he hadn’t thought they’d be this poor. It was one thing to tighten and brush a loosely woven bolt into an evenly stretched length of cloth. It was another to make a silk purse from a sow’s ear, as Granny used to say.

He turned to the fulling mill’s next customer, a simpering lass of no more than sixteen who flickered her eyelids so much he feared she had a sty. At least her bolt showed more promise than the last. He recorded her name and what the cloth was to be used for.

The next customer placed her bolt of cloth onto the table. The fabric glided over his fingers and draped across his palms. Wool finely spun and woven into a silken fabric. Mouth open, he savored the sensation a moment before looking up. And up. At the tallest woman he’d ever seen, her eyes almost level with his own when he straightened.

Light-brown hair framed her face beneath a wide-brimmed straw hat. Hazel eyes that matched her hair assessed him from under arched brows.

He shut his mouth and cleared his throat. “This cloth is outstanding.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I have not seen the like in, well, maybe I have never seen the like.”

She lowered her head, but not fast enough to hide the blush. Not a beautiful woman, but handsome enough with that pink on her cheeks.

“The weave is distinctive, and the fibers so finely spun.”

“My papa taught me the weave pattern, his own creation. The wool comes from the town’s flock of sheep.”

“You spun the wool yourself?”

“I did.”

Both spinner and weaver, was there no end to this woman’s talent? An older woman behind her coughed. He was staring. He grabbed an order slip and dipped quill to ink. “For what purpose do you wish the cloth prepared?”

She paused a moment. “My sisters are in need of new gowns. I pray there shall be two dress lengths.”

“Quite possibly.” But why not a gown for herself? The dress she wore was plain, a work dress covered by a starched linen apron. Well made, but not the quality of the fabric in front of him. “Your name?”

“Miss Yarrow Fenn.”

Yarrow? What an exotic name. He scratched it on the order.

“As you can see, we are taking in many orders today. I cannot say exactly when yours will be ready, but check back in about ten days.”

“I will, sir, and thank you.” She turned and walked away, a study in graceful movement. The long fringe of her shawl swayed with each step.

Another cough from the elderly lady next in line. He blinked. She gave him a toothless grin and plopped her misshapen bolt on the table.

***

Yarrow hurried past the front door of the house and around back to her sanctuary. She entered and inhaled the mellow scent of lavender. A smile played across her lips as her fingers caressed the wooden beam of the loom. This was her domain. Her spinning wheel, brought over from Wales by her mama’s mama, sat in one corner near a window. Yarrow’s narrow bed stood against the opposite wall, another window over it. An oaken chest, built by her papa’s papa, held her few personal belongings under the third window. The luxury of glass windows, three of them no less, gave her natural light by which to create the fabrics that kept her sisters’ families clothed.

She had plenty of linen spun to dress the loom but needed to spin more wool to weave through the linen warp. This next cloth would be sturdy stuff to make breeches for both brothers-in-law. With the sheep shearing finished last week, her fingers itched to begin spinning.

A knock rattled the door connecting her refuge to the main house. “Yarrow, have you returned?” Penny asked.

“I have.” Yarrow straightened her apron and braced herself for whatever might come before she opened the door.

“What took so long at the fulling mill? You had only to drop off your bolt and return.”

“The line was long before I arrived and plenty more behind me. The mill will do a good business.”

“’Tis all well and good, but I need you to start supper.” Penny sighed as though auditioning for a traveling thespian troupe. “Once ’tis started, run and fetch Marigold.”

“Is there something I can—?”

“You know nothing about having babies. Tend to supper and then fetch our sister.”

Yarrow bit her tongue. Their mama had passed away while Penny was barely walking, leaving the two older sisters to raise her. And spoil her. Pregnancy made some women bloom while others. . . Hopefully, Penny’s disposition would sweeten once the babe arrived.

Yarrow entered the main house and crossed to the hearth. Built of native rock, it encompassed the entire west wall of the main room. She busied herself putting together a simple stew with a bit of leftover venison. She wrinkled her nose at the equally wrinkled potatoes, thankful they’d been able to plant the early crops in the garden last week. She pushed the stew near the fire where it would cook while she fetched Marigold.

A brisk walk through the settlement confirmed that spring was well underway. Dandelions dotted the meadow where the sheep grazed, watched over by the boys hired to tend them. Each spring the sheep were forced into the river for a short swim to wash the worst of the dirt from their fleeces. Once dry, they were sheared and the wool sold, which kept the settlement taxes low.

Since King William III had signed the Wool Act, however, they could only sell the wool within Connecticut Colony or to England herself. Sales to other colonies or any other ports were prohibited. Not only the wool but anything made of it. Taxes collected at both the port in Connecticut and again at the port in England destroyed any profit. Now they kept only enough sheep to supply buyers within the colony.

Including Yarrow.

With the weather so fine, she loved to sit outside and card the wool in preparation for spinning. Maybe this year she’d teach Marigold’s oldest daughter to help her. With her niece’s help, she could spin more yarn and weave more cloth to be taken to the fulling mill. A flush warmed her neck. She was interested in producing more cloth to sell and work toward her independence, not as an excuse to visit the fulling mill.

Or to see the admiration in the piercing blue eyes of one Mr. Peter Maltby.

paperback ISBN: 979-8416917975 – ebook ASIN: B08XPT7DGB – audiobook ASIN: B0CY3SHJ11

Return to https://peggthomas.com/