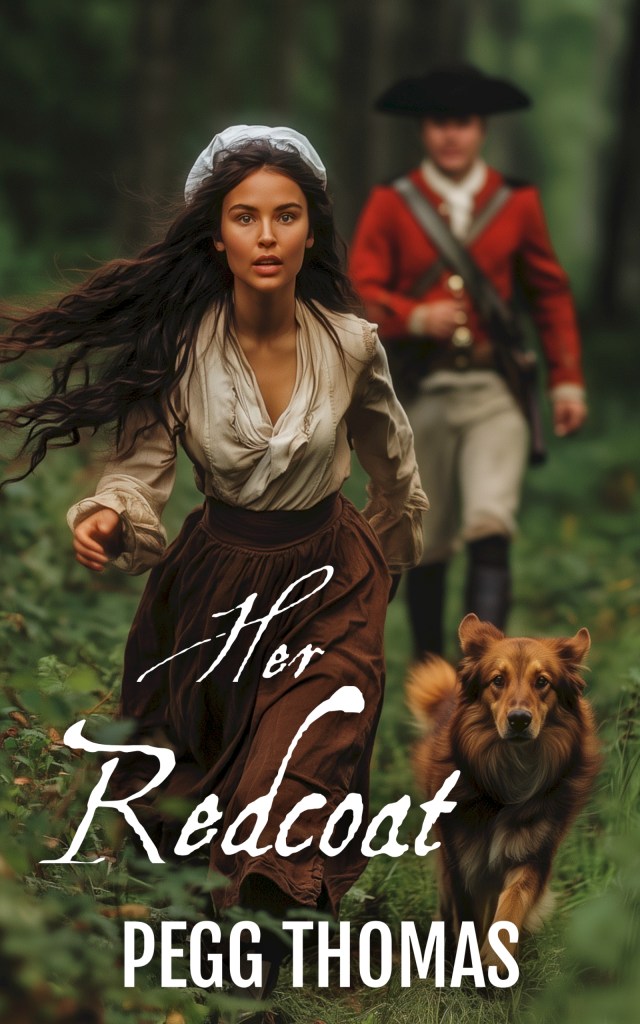

a novella

Originally published in The Backcountry Brides Romance Collection

The daughter of a fur trader, Laurette Pettigrew grew up in the northern frontier. Hers is a lonely existence avoiding the British in the fort and the French voyagers who populate the area in the summer months. The local Ojibwe are her only friends.

Sickly and weak, Henry Bedlow arrives at Fort Michilimackinac against his will. He wears the red coat and shoulders a musket, but in his heart, he isn’t a soldier. But his choices were to join the army or prison.

Their chance meeting changed everything. Will a deadly clash of cultures keep them from finding happiness?

Tropes: Slow-Burn Romance – Cross-Cultural Romance – Wounded Hero – Strong but Vulnerable Heroine – Forbidden Love – Protector Romance

Chapter 1

Early Spring 1763 – near Fort Michilimackinac

Laurette Pettigrew’s father limped away from their cabin. He turned to give her one last wave before he was swallowed by the tall pines and budding brush of the surrounding forest. She was alone. Months of isolation stretched before her.

A wet nose pressed against her clenched hand. Laurette relaxed her fingers and tangled them in the wiry hair around the tall dog’s ears. Not quite alone. Thank goodness Papa had taken the puppy in trade in the fall after Mama’s death.

″We are on our own, my friend.” Her voice broke the early morning stillness. “You and I, we are banished from the settlement.”

Charles Pettigrew owned a trading post in the settlement outside of Fort Michilimackinac. Since last fall, Laurette had helped Papa with the business. They’d lived in the simple room tacked onto the back of the trading post all winter. She’d cooked, cleaned, sorted merchandise and, on the rare occasion a British soldier visited the post, she’d hidden in their room.

Until yesterday.

Reports that voyageurs had been sighted nearing Fort Michilimackinac changed everything. Their boisterous voices carried over Lake Huron, oars striking the water in rhythm with their songs, announcing their arrival. They appeared as a mass of large canoes skimming waters just off shore. Men had leaped from the vessels into the rolling white-capped waves, laughing and shouting. But Laurette had not been allowed much time to behold the sight.

Papa had left the trading post in the hands of his apprentice and hustled Laurette back to the cabin two miles south of the fort. The cabin she and Mama had shared in the past. At least he’d stayed the night with her. One last evening before the loneliness closed in.

″Papa, how can you leave me?” she whispered into the stillness.

Because the voyageurs would stay for many weeks, until gold and crimson edged the leaves again. Harsh men, strong men, men her father didn’t trust near a daughter old enough—past old enough—to be married.

She turned toward the cabin, its logs sturdy and straight. She hadn’t been back since Mama’s death. The logs were gray with age, the bark mostly peeled away. One side wore the scars where a bear had tried to enter, probably searching for a place to make its winter’s den. Bark overlapped on the roof to keep out rain and snow, including a fresh piece Papa had used to repair a corner when they’d arrived.

The cabin looked forlorn, lost… empty. What had always been her home had now become her prison. Or would be, if she followed Papa’s orders to remain there all summer. Alone except for Marie.

Laurette entered and scraped the last of the warm rice porridge into a shallow wooden bowl. “Here, Marie.” She set the bowl on the hard-packed dirt floor. “We will fish for our supper, which you will enjoy much more, n’est-ce pas?”

The dog wagged her tail as she lapped up the porridge.

Laurette dipped hot water from the large kettle kept near the fire and washed the few dishes, including Marie’s bowl when she was finished, and then scanned the inside of the cabin. Papa had filled both large buckets from the creek that ran behind the cabin before he’d left. There was a lot of cleaning to do. They’d chased a squirrel out when they’d arrived. It had obviously wintered inside. It would take a full day to remove what was destroyed, repair what she could, and clean everything.

But even repaired and cleaned, it wouldn’t be home without Mama.

She dropped onto the bench. What to do first? Elbows on the table, she rested her chin on her hands. What did it matter? Marie jumped onto the smaller bunk on the cabin’s back wall, turned around three times, and dropped onto the holey remains of its mattress. Laurette squashed the urge to do the same. To lie down and wait for summer’s end, for the voyageurs to paddle away, for Papa to come and fetch her. To be part of the small settlement again. To end her time of exile.

Instead, she rose and opened the satchel she’d packed in haste before leaving the settlement. From the center, cushioned between her folded skirts, she pulled out a book. Its leather cover was cracked, the edges tattered. She opened it, its yellowed pages stiff and fragile. Her mother had treasured this book, even though she couldn’t read. How often had she watched Mama rest her hands on the cracked leather, her lips moving without sound, at peace with herself? The book wasn’t magical. Mama hadn’t believed in mystical things, unlike their Ojibwe friends. She’d believed in Jesus. Mama had said the book told about Him.

If Laurette could read the words printed within, maybe she wouldn’t be so lonely for the long summer ahead. Maybe she’d find the peace Mama had found and be content with Papa’s absence and her solitude.

Or maybe when the Ojibwe returned to their summer village, her friend’s brother Makade-Waagosh—Black Fox—would present her with another option, one that he’d hinted at before the tribe left last fall.

***

Henry Bedlow stood at attention at the end of his cot in the fort’s infirmary, doing his best not to cough.

″You have been here for a fortnight, and all you have accomplished is to lie on that cot and consume the king’s provisions.” The regimental surgeon paced in front of Henry, hands clasped behind his back. “You require movement to rebuild your muscles. If you do not get yourself into some semblance of fitness, you shan’t be worth a pile of rotted beaver pelts to this regiment.” He pivoted and glared at Henry. “Is that understood?”

Henry waited for the surgeon to either continue with his current diatribe or launch into a new one. Heaven knew the man had an arsenal of them. And having arrived in his sickly state, several had been directed at Henry. The surgeon was one of the soldiers he wouldn’t miss when his time of service was completed.

″Walk thrice around the fort each morning and thrice each afternoon until further notice, taking in the fresh air and exercising your limbs.” He thrust a finger under Henry’s nose. “Not inside the fort where you would be in the way of our industrious soldiers, but outside the palisade.”

Henry suppressed the urge to protest, having learned early on in His Majesty’s army that it would do no good and possibly much harm.

To the north, beyond the fort’s high wooden sides, stretched a strip of beach that went as far as the eye could see to both east and west. The forest to the south was like something out of medieval times, deep and foreboding, stark with winter’s lingering grip. Henry had been awed by the sight as he’d disembarked from the canoe that had carried him to Fort Michilimackinac. Certainly nothing like the gentle woodlands of his native England. It concealed within its darkness heathen tribes—the same savages who had sided with the French in their recent war against the Crown for the American Colonies.

The surgeon smirked, his pale lips pulled thin. “Worried about the Indians? Good. ’Twill keep your feet moving.” He motioned toward the door. “No better time to start than the present. Dismissed to walk.”

Henry snapped a salute and then relaxed for a moment after the surgeon moved on. As much as a man could relax who’d just been told to walk among the heathens and wild beasts of an untamed land. Would he be allowed to carry his musket, at least?

″He were a mite rough on ya, if ya ask me.” Willie Harris raised himself on his elbows from the cot next to Henry’s. “Like ta see him marchin’ round outside the fort.”

″He is correct, however.” Henry tugged at the belt that kept his breeches on his gaunt frame. “I shan’t improve without some meat on my bones.”

″There’s puttin’ on meat, and then there’s fattenin’ ya up for the animals out there.” Willie jerked his head toward the south. “If the four-legged fail to get ya, the two-legged will.”

Henry couldn’t argue with that. He’d seen a few Indians from the window of the infirmary, dark-skinned warriors dressed in a haphazard combination of animal skins and woven cloth, some with feathers in their hair, some with little hair at all, just a circle at the top of their heads from which grew a single, tied-back lock. He’d heard some Indians painted their skin garish colors, but not those he’d seen.

Talk around the infirmary was that the tribes would return soon from wherever they went during the coldest months. More Indians. Some said they’d be hungry from the long winter, like the great black bears known in the area. Wonderful. And Henry walking into who knew how many of them.

Of course, you couldn’t believe half of what was said. To hear some soldiers talk, Indians were all eight feet tall with legs like tree trunks and pointed teeth like a cat. Those Henry had seen were average height and lean, even wiry-built men. Of course, he’d not been close enough to see their teeth.

Like it or not, one did not disobey orders in the army. He tied thick wool leggings over his breeches and hose and grabbed the well-worn red coat he’d been issued so many months ago. He pulled his hat from its peg on the wall and snugged it onto his head. At the doorway, he pulled a musket off the rack and slung over his shoulder. He wasn’t leaving without one, no matter what the surgeon thought.

He fervently hoped he wouldn’t need to use it.

paperback ISBN: 979-8413910535 – ebook ASIN: B09RW8CGDG – audiobook ASIN: B0DT38TWHG

Return to https://peggthomas.com/