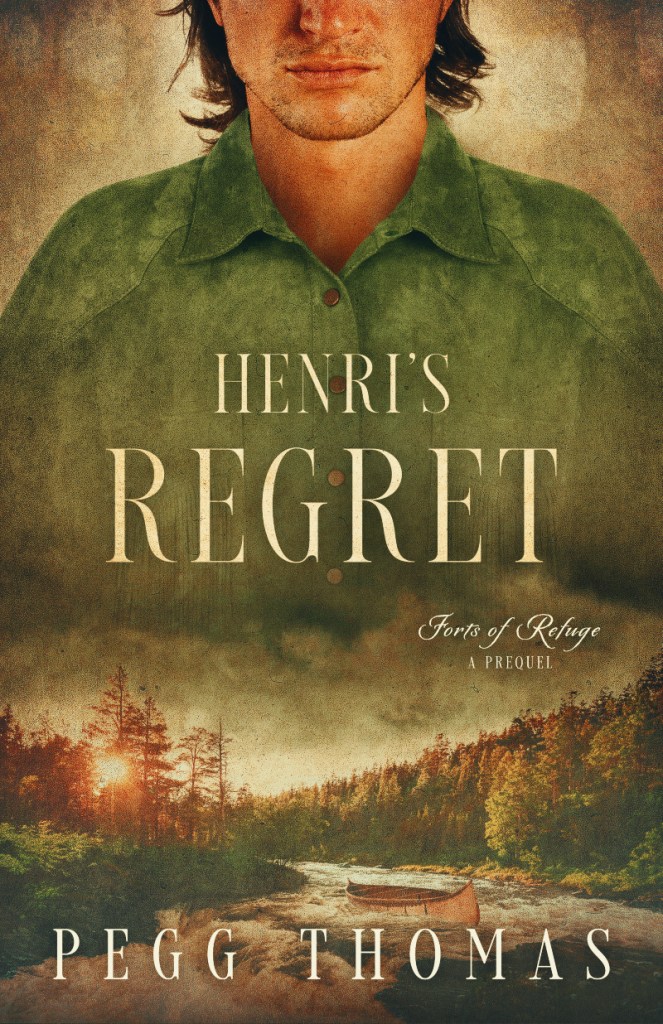

Forts of Refuge – Prequel

Frenchman Henri Geroux can’t sign the oath of loyalty to the British after the end of the French and Indian War. He leaves his home behind and sets out on an adventure with his Ottawa friend, Dances Away. But heading west to trap beaver doesn’t mean he outruns his problems. Faced with a dangerous journey into an unknown land, he and Dances Away get caught up in more than they’d bargained for.

A prequel to Maggie’s Strength

Tropes: The Journey – Cross-Cultural Tension – Cross-Cultural Romance – Cost of Conviction

Chapter 1

“I cannot stay on this land to be controlled by the British overlords.” Henri Geroux pointed to the split-log flooring of the cabin built by Père on land granted to him by the French government. “Neither should you. Come with us. Come with me.”

Baptiste Geroux shook his head, the stubborn lines of his face set. “I would only slow you down.” He smacked the side of his lame leg.

“That leg hardly slows you at all.” Why must his brother fall back on that excuse? He was lame, but not disabled. He managed the farm with little help from Henri. Very little. Guilt pressed against the backs of his eyes and started a headache.

“It does not slow me behind the oxen, non. But they are slow already.” Baptiste’s mouth twisted into a wry grimace. “Hostile Indians, they would not wait for me, as Beau and Pierre do.”

There was truth in the words, but not the truth Henri wanted to hear.

“And what would happen to Beau and Pierre if I leave with you, eh?”

Another reason he’d never be able to talk his brother into going—the oxen. The team was the last of the line of oxen Père had raised. Baptiste treated them as if they were members of the family, and though Henri didn’t share his sentimental attachment to the animals, he had no wish to see them in some Ottawa’s cooking pot either.

Neither did he wish to leave his brother behind.

“You know the British will make you swear an oath of allegiance—you, a Frenchman.”

Henri couldn’t sign the oath. He’d worked as a scout for the French during the war. If he or his name were recognized, he could be shot. Or worse, hung.

“Their deadline to sign is almost on top of us.” He pointed at Baptiste. “And afterward, they will treat you no better than a dog. You will be forced to sell your produce to them at the fort.”

“I know.” Baptiste sank onto the edge of the bed in the cabin’s main room. The bed that had belonged to their parents, and then just Père. Empty now these past months. “But I must sign to remain and work the land Père left to us.”

“You will not be loyal to the Redcoats.” It wasn’t a question. Henri’s brother was as staunchly French as he was.

“Non, but if they leave me alone, the same I will do for them.”

The headache blossomed, and Henri pinched the bridge of his nose. If he were the son—the brother—he should be, he would stay. But to give an oath to the British? Even if his past deeds weren’t discovered, to forever stumble behind a plow, or swing a scythe, or shuck corn to feed the Redcoats at the fort? Non.

The Ottawa had the right of it. A man should live free. Henri wanted to see the land beyond the big water. He wanted to run free beneath the forest covering, to hunt wild game rather than tend oxen and scratch in the dirt.

To be a hunter and a warrior instead of a farmer.

Although his best friend, Dances Away, would travel with him, Henri also wanted his brother by his side. He tried one last plea. “What would Père say about you taking an oath to the British?”

Baptiste stared out the window. The spreading oak that shielded the graves of their parents and little sisters wasn’t visible, but he was facing that direction.

The cabin grew quiet. All Henri could hear was the thumping of his headache. When he could take no more, he strode to the door and grasped the handle.

“Wait.” Baptiste’s voice was calm, his tone even. “I think Père would be disappointed that I could not discourage his youngest son from leaving the land he loved and the farm he spent his life establishing. The land he and Maman are buried beneath.” He raised dark eyes filled with sadness. “As I am disappointed in myself.”

“This has nothing to do with you, brother.” Henri wrenched the door open and let it slam behind him.

He stepped off the porch into the heat of the sun and the humid fall air. The land before him grew straight rows of corn, hardy and green. Beyond the corn remained the golden stubble of wheat, rye, and barley crops that had grown in their long tracts, with the tract of tangled pea vines being closest to the river. Baptiste would have to gather in the peas and corn without Henri’s help.

Little as that was most of the time.

But it couldn’t be helped. As much as he loved his brother, Henri couldn’t stay. Couldn’t swear the oath of loyalty to a hated people. People who not only hated the French, but the Ottawa as well.

He ran his hands down his fringed buckskin coat and glanced at the Ottawa-style moccasins encasing his feet below the leather leggings and breechclout. He was overdressed for an Ottawa in the summer heat, but he looked more Indian than French, as did many of the Frenchmen who’d lived in this part of Canada for any length of time. They had adapted to the land and befriended the native people.

Henri more than most. Maybe more than was good for him.

Now it would cost him his brother.

***

The distance from the farm to the Ottawa village could be covered in half an hour at a run. Henri had shed his coat, linen shirt, and leggings as soon as he’d entered the forest, leaving on only his breechclout. He approached the village with the rest of his clothing in the satchel he had slung across his chest. He ran with ease, the exercise having removed his headache, his bare torso and legs tanned to almost Indian darkness, sweat streaming freely over his skin.

He felt more alive than he could ever feel behind a plodding pair of oxen or in the middle of a field, harvesting crops.

When he reached a village guard, Henri slowed, breaths coming deep and even. “Aniin,” he greeted the warrior watching him from beneath a tree. Henri was as fluent in the Ottawa language as he was in French, having grown up around people who spoke both.

The guard straightened, hand on the hilt of his knife. “What brings you here?” Although Henri knew who the man was, they were not friends, the guard being half again Henri’s age and one who did not think highly of any white man, not even the French.

“Dances Away waits for me.” Or at least Henri hoped he did. If his friend’s older brother hadn’t succeeded in talking him out of their plans to go west.

“What took you so long?” Dances Away appeared in the path ahead, his usual grim expression offset by the spring in his step.

The guard jerked his head in the direction of the camp, giving permission to enter.

Henri jogged to Dances Away. “Walking Fire Stick offered no objections?”

“I think he is happy to see me go.” A rare grin creased his face. “Speckled Lion has made an offer of marriage for Woman of the Waves. Her father has spoken to my brother and suggested I should journey somewhere else for the summer. He must think it will take that long for Woman of the Waves to accept.”

“Can you blame her?” Speckled Lion stood out as glum among a people who tended to be dour by nature. Henri had never seen him smile or heard him speak in anything other than a harsh tone.

Dances Away, by contrast, was several years younger, better looking, and known for his good humor and charming ways. Perhaps too charming, on occasion. He’d managed to avoid marriage thus far, but he had more than one young woman of the tribe sighing when he strutted through camp.

For that matter, so did Henri.

Often enough, he’d had to sit through Père’s lectures about that. And for the last few months, Baptiste’s. As if he’d take an Ottawa woman to wife.

He was a Frenchman. Although, there were times when he felt strongly drawn to the Indian way of life. Never more than when the British loomed across the river.

But Maman had made him promise, along with Baptiste, that they would marry from among their own people. It was a promise—made to her on her deathbed—that he intended to keep. No matter how charming the young Ottawa women were.

Dances Away thumped him on the shoulder, breaking Henri out of his thoughts.

“I cannot blame her for preferring the better man—me,” Dances Away boasted.

“And yet, you are traveling west with me.”

“Are we not brothers? Where you go, I will follow.”

Henri tipped his head to the side and studied his friend. “And?”

“Woman of the Waves is not my choice for a wife.” He started walking into camp and leaned closer when Henri stepped along beside him. “She snores.”

Henri wasn’t about to ask how he knew that.

“But enough about women.” Dances Away waved an arm at the camp that unfolded before them as they entered the clearing. “We have a journey to prepare for.”

“We do.” He couldn’t quite match his friend’s tone of anticipation.

Dances Away glanced at him, one black brow raised. The man could ask a question without a word when he did that, a trick Henri had never mastered.

“I had hoped…” He shrugged.

“I told you he would not come. He is wiser than his little brother.”

“That limp does not slow him—”

“It would slow him enough, and he knows it, even if you will not admit it.” They reached the summer wigwam Dances Away shared with his brother, his sister, and their mother, their father having died years ago. The older brothers had married and moved to their own wigwams. He waved for Henri to sit on the low platform piled with furs before settling across from him. “We will carry heavy packs, our weapons, and enough pemmican to see us over the big lake to the pointed bay beyond. Baptiste would struggle under such a load.”

“But the canoe will hold our belongings.” It was deep and wide but light enough to race across the water, being constructed of birch bark layered over white cedar supports, sewn with black spruce roots, and sealed with a mixture of spruce gum, charcoal, and bear tallow. They’d been working on it since the grass had begun to green and had finished it last evening.

“For much of the journey, but we will have to portage rivers once we continue past the pointed bay.”

He didn’t relish carrying their belongings—and the canoe—when the river was too rocky or when a waterfall interrupted it. During those times, they would be the most vulnerable to attack by hostile tribes.

As much as Henri hated to admit it, Baptiste would have struggled to haul his share of the burden.

His brother might have been right, but Henri didn’t have to like it. Nor would it change his mind. There were risks to taking their trip, but the risks of staying were too high.

***

Henri and Dances Away hovered at the edge of the circle of men seated in the center of the Ottawa camp. The elders had gathered to discuss news brought by a runner from another camp east of them. The runner was well-known and trusted, and when he rose to speak, he had everyone’s quiet attention.

“Two years ago, the British retook the fort at Niagara. Last year, they took control of Montreal. Since then, they have continued to creep west, even to the fort across the river.” He pointed toward Fort Detroit. “Now we have heard that they are to have a new king, one called George the Third. They say he will be a harsh king, that his soldiers will be many, like the sand on the shore.”

Discussions broke out around the circle. The Ottawa didn’t like that their people hadn’t been able to stop the westward flow of the British. Neither did Henri. He wasn’t proud of his own people either. The French should have been able to protect and hold what was theirs—New France.

The runner raised his hands until the voices died down. “But there is unrest among the settlers. Though they are British themselves, they are unhappy with the laws made by their old king, and they have little trust in the new king. There are rumors of an uprising among them.”

That brought another round of discussions among those gathered. The Ottawa were used to the idea of the French king, who they understood lived across the ocean. He sent gifts and tributes to the Indians with the Frenchmen who came to buy their furs and work their lands. He allowed them to trade for metal knives, metal pots, woven cloth, brandy, and even the most coveted of all—muskets, lead, and gunpowder.

The British king had done no such things—and he was despised.

Chief Pontiac rose. His commanding presence stopped all conversation. He wasn’t physically much different than the other warriors around the inner circle, but the way he held himself spoke louder than words. This man was their leader, and they would listen to him.

Henri had never been easy around the man. There was something unsettling about his charisma.

“Let the runner finish his story,” Pontiac said and then resumed his seat.

The runner continued. “With the British distracted on both sides, from the French and the People on one, and from the American settlers on the other, my chief plans to increase his support of the French settlers fighting in our area. He wishes for the People here on the river’s shore to do the same. He asks for the great chief, Pontiac, to take up his warriors and fight.”

There arose a cry from almost every throat at the fire and beyond.

Henri caught the eye of Dances Away. His friend gave the briefest shake of his head, mouthing tomorrow we leave.

Good. Their journey would continue as planned, no matter what Pontiac intended to do in response to this plea for more warriors to fight.

But could Henri leave Baptiste behind now? Their farm would be in the crossfire, between Pontiac’s Ottawa camp and Fort Detroit. Baptiste would be in harm’s way. And alone.

Henri had one more night—armed with this news—to try and talk him into going west.

***

“He will come,” Dances Away said.

Henri wasn’t so sure. He and Baptiste had argued late into the night, but nothing had changed. His brother would not leave, and Henri could not stay. They’d not slept until the wee hours of the morning. Baptiste had risen early, as he always did, and tended to the oxen before working in his fields.

Instead of assisting, Henri had come to the Ottawa village to fill their canoe with everything he and Dances Away needed for the next few weeks, plus traps for beaver, warm clothing for the winter, and trade goods for the Indians they would meet. Despite the morning’s muggy heat, fall’s cool weather was just around the bend. The vessel was filled, oiled hides wrapped and tied around their precious cargo, and Walking Fire Stick was bidding them a safe journey when a shout reached them.

Baptiste hurried toward them in his limping gait, waving something. “I am sorry to be late, it took me too long to find this.” He stopped in front of Henri and pushed the red knit cap into his hands.

Père’s cap.

Knitted by Maman.

A knot tightened in Henri’s throat as Baptiste pulled him into a rough hug.

“Let it bring you luck on your journey. And let it see you safely home.”

Henri stepped back. “Thank you.”

“Now go.” Baptiste pointed to the laden canoe on the river’s edge. “Give the British time to forget about the war and who fought on which side. Trap enough beaver to fill your canoe. Return a rich man. I will be here, waiting for you.”

Walking Fire Stick motioned for them to get into the canoe, which was in the water but resting on the sandy bottom, heavy with gear. Dances Away settled into the front, so Henri took the rear. The two older brothers waded in and, after mingled grunts and a mighty shove, the vessel slid free of the bottom and bobbed on the current. Henri dug his paddle into the clear water, turning the vessel parallel to the shore.

He raised a hand in farewell.

Baptiste replied in kind, standing there unmoving, growing smaller as Dances Away and Henri found their rhythm with the paddles.

Would Henri ever see his brother again?

But Baptiste had never asked Henri to stay. They both knew the dangers—if he’d stayed or if he’d gone. And Henri preferred his chances in the west.

Henri had been on the northern lake before, with Dances Away and with Baptiste, but this time, he and Dances Away were paddling its length straight across, the shorelines barely visible on each side. Gentle waves rocked the canoe in a soothing motion while the breeze cooled Henri’s skin. The rhythmic motion, the seagulls turning lazy circles overhead, and the late August sun beating down lulled him into a drowsy state.

“Land ahead,” Dances Away said. “The opening to the upper river.”

Henri stretched to see over his friend’s shoulder. “Do we camp there tonight?”

“What is the matter?” Dances Away chuckled, the sound like gravel cascading over rocks. “Are you tired already?”

“I am hungry.” And maybe a little tired. It’d been a long time since he’d spent a full day in a canoe, his long legs curled underneath him. But he wasn’t about to admit it.

“As am I.” Dances Away pointed to the western bank of the river ahead. “We will stop there.”

“Why on that side?”

“Anyone we meet there should be Ottawa.”

“And on the other?”

Dances Away shrugged. He either didn’t know or didn’t want to talk about it. The Ottawa man was like that, but Henri was used to his ways, having been raised as close to brothers as two boys of different cultures could be.

Soon they entered the river and brought the canoe through a patch of concealing cattails onto a pebbly shallow cove. Brown and silver bodies darted from their shadow. They would eat well that night without touching their stored food.

Dances Away stowed his paddle and leaped into the water.

Henri did the same, the cool water coming above his knees. He stretched his legs and flexed his ankles to work out the kinks as they hauled the canoe to shore. With a heave and a shove, he helped Dances Away beach the vessel, then unwound a length of rope and tied the front of the canoe to a nearby bush.

Arms came around him. Henri was lifted off the ground and flipped through the air. He landed in the shallows with a splash, instinctively holding onto his attacker and raising his legs to kick the man up and over into the deeper water before Henri’s head went under. He twisted and rose, arms out to balance himself, blinking the river water from his eyes as Dances Away surfaced.

The Ottawa man shook his long hair, spraying river water in all directions.

“You scared away our dinner,” Henri said.

“Only the small ones. The larger ones, the brave fish, they will return.” Dances Away pointed at Henri. “And you needed a bath. You smelled worse than a striped weasel.”

There may have been some truth to that.

He’d shucked down to just a breechclout before they’d left the lower river, but the exertion, humidity, and broiling sun had worked together to cover him with sweat. He flipped onto his back and pushed one foot against the river bottom to float toward the cattails.

“Since I must bathe, it is up to you to catch our dinner.” He grinned at his friend.

Dances Away plunged under the water and came up next to Henri, settling on his back and floating along with him. “We both need a bath, I think.”

It was almost as if they were stripling youths again, carefree and indulging themselves. But in Henri, there was an undercurrent of uncertainty. Had he done right to leave his brother behind? Should he have stayed and tried to avoid the British? Should he have shouldered his share of the burden of the farm Père had left to them?

But it was the wilderness that called to Henri—not the soil.

If they trapped many beavers and made money, he would share it with Baptiste. Purchase him another set of oxen or a new plow. Assuming the British didn’t expel his brother from their land.

And assuming Henri survived to return.

***

The better part of two days toiling against the river’s current brought Henri and Dances Away to the big lake. Neither had ever been this far north, but they’d heard the stories around many a campfire from the Ottawa men who’d made the journey. Henri had also heard stories from Frenchmen, both soldiers and traders, who had been there.

None of those stories had prepared him for the vastness of the water spread before them.

Waves large enough to capsize their canoe, capped with white foam, rushed toward the western shore. A flock of geese rode the waves, disappearing and reappearing with the action. The wind roared across the water’s expanse. And to the east, billowing dark clouds stacked against the early evening sky.

“We had best make haste to the shore and secure the canoe,” Henri hollered above the wind.

Dances Away dug his paddle into the water, and Henri turned the canoe toward a sandy stretch of beach flanked by large trees.

A bolt of lightning stabbed from the clouds to the water, followed by a long rumbling that Henri felt to his bones. It added extra strength to his arms as he fought the waves and steered the canoe so they wouldn’t flip over.

At last, the waves started working in their favor, and they rushed to the shore, the canoe’s bottom dragging to a halt on its sandy edge.

Dances Away pointed to a chest-high ledge where the forest towered over the sand. “We must get the canoe up there or risk its being pulled out by the storm.”

They couldn’t carry it loaded, so this would be their first portage, of sorts. They pulled the canoe as far onto the sand as they could, then hauled their cargo to the ledge and tossed it up. They returned for the canoe and carried it upside down on their shoulders, fighting the wind that tried to snatch it away. They heaved it onto the ledge and climbed up after.

Dances Away rolled the canoe onto its side, bottom to the wind, and stowed their belongings inside while Henri unrolled two oiled hides and anchored them with rope to nearby trees to form a canopy. He ducked under the hides and into the canoe as the first thick raindrops battered them.

“It is a good thing the Ottawa are superior builders of canoes.” Henri thumped the carved cedar support over his head.

“And makers of pemmican.” Dances Away handed over a pouch filled with a mixture of dried fruit, shelled nuts, dried meat, and bear fat. “There will be no fish for our supper tonight.”

Henri scooped out a handful of the essential travel food and chewed a mouthful. It wasn’t bad. It filled the stomach and would give them energy for the next day. He licked the remains of the greasy meal from his fingers as the storm unleashed a load of hail.

Icy balls the size of hickory nuts bounced on the forest floor outside the oiled hide covers and pounded on the exposed ends of the canoe.

Dances Away frowned. “We will have to inspect the birch bark and seams before we travel tomorrow.”

“At least we have a pot of spruce resin with us.” He thumped his chest. “And a French iron pot to heat over the fire. The Ottawa canoe and the French pot are a good combination, my friend.” But they would get a later start than normal after heating the resin and sealing whatever damage the storm was doing to the birch bark.

They made themselves as comfortable as possible in the cramped confines of their canoe shelter, prisoners of the storm. But they had plenty of time to reach the pointed bay and build a winter shelter before the snows came. Then they would have the whole winter to trap beaver—living wild and free.

***

A smudge of smoke feathered above the stunted trees behind the sandy beach to their left. When Dances Away made the signal to keep silent, Henri nodded, then scanned the shoreline for any hint of movement. They’d reached the middle of the big bay on the sixth morning after first entering the huge lake and had turned their canoe north again.

But who was on the shore?

According to the Ottawa who knew the area, there were no tribes living there during the summer months. It was marshy and flat, not well-suited to summer occupation. And the mosquitoes would have eaten them alive if Dances Away and Henri hadn’t kept the canoe away from land. Even so, Henri had donned his linen shirt for relief from the strongest of the biting insects that chased them.

The bigger problem was that whoever was tending the smoky fire would have an unobstructed view of the canoe if they came to the beach. And sure enough, Henri and Dances Away were barely past the smoke when a shout of alarm broke out. Indians broke through the trees onto the sand.

“What should we do?” Henri didn’t recognize the tribe from their clothing, and they were too far away to make out any words.

“There are no canoes on the beach. Even if they have them hidden in the forest, it will take time to launch them and follow. I say we paddle—hard.”

More Indians ran onto the beach, but Henri and Dances Away had perfected their rhythm, and their canoe skimmed over the water. Distant shouts reached them, but a glance back said no one pursued.

Once out of sight around a finger of land that jutted into the lake, Dances Away let his paddle rest on his lap and twisted to look at Henri. “I am certain their clothing was northern Ojibwe. What could they be doing down here this time of year?”

“Perhaps they also had a runner come and ask them to join forces and fight the British.”

Dances Away’s dark eyes flashed in the early evening light. “I want to know.”

“Know?” Henri slapped a mosquito. The annoying insect popped against his thigh, leaving a smear of blood. “Know what?”

“Why they are here.”

“Are we just going to walk into their camp and ask?” And maybe get themselves shot through with arrows or tomahawked for their efforts.

Dances Away shook his head. “We will sneak up once it is dark and see what we can learn.”

“Sneak up… on a passel of Ojibwe?” Henri couldn’t keep his voice from rising at the end. He’d not mastered stoicism as well as his Ottawa friend.

“It will be the first test on our journey. To sneak in, listen and watch, and sneak out without being seen or heard.”

“They will have guards posted, will they not?”

“We will watch for them.”

“What does it matter why they are here?” Henri wasn’t trying to be uncooperative, but it didn’t seem prudent to test themselves and their survival skills without a solid reason.

“If we can learn why they are here, it might tell us if others are gathering. Knowing that could save our lives, should we stumble across the wrong tribe.”

Any tribe could be the wrong tribe for Henri. While most of the Indians in this area used to be friendly with the French, they’d been let down by the string of losses the French had suffered against the British. It made them look weak. And the gifts and tributes had greatly diminished as many Frenchmen moved back to France, or at least to more securely held French territories.

“All right, but if you get me killed before we even reach the pointed bay or gather a single beaver pelt, Baptiste will never forgive you.”

Dances Away grinned and paddled for shore.

They hid the canoe in a swampy area where they could get into it fast and push off without having to launch it. Just in case. Ignoring his friend’s disapproving scowl, Henri donned his leather coat and leggings. He’d rather sweat than be eaten by insects, and the coat covered the whiteness of his linen shirt. Then he followed Dances Away—dressed only in his breechclout—from the swamp to the forest where they’d seen the Ojibwe.

Darkness had gathered around them by the time Henri caught a whiff of smoke.

Dances Away tapped his arm and pointed to their left.

Squinting into the gloom, Henri could just make out the silhouette of a man squatting beneath a tree.

A guard.

Dances Away double-tapped Henri’s arm, then moved forward, bent low, hands feeling the way forward.

Henri followed, concentrating on placing his feet so they didn’t make a sound. Within minutes, voices reached them. Male voices.

A lot of them.

He and Dances Away were almost crawling by then, hands and toes on the ground, feeling their way closer to the fire that crackled in the middle of a natural clearing. Around it sat men—without a woman in sight. This was not a hunting party or a tribe on the move.

These were warriors.

Dances Away cocked his head, but Henri didn’t need to. He’d always been blessed with exceptional hearing, a trait that had gotten him in trouble more than once in his youth.

The talk around the fire in the Ojibwe dialect was easy enough for Henri to understand. It wasn’t tense, it wasn’t urgent, but it was clear the group was there for one purpose—to scout around Fort Detroit and report back to their chief what they found.

After several minutes, Henri backed up and Dances Away followed. Relief that they’d pulled off the stunt nearly weakened Henri’s knees when they reached the canoe.

“Not a war party—not yet,” Dances Away said.

“I will still sleep better tonight if we paddle on for another mile or more.”

“There could be another party of warriors ahead.”

“Perhaps, but there is for sure one behind.”

Dances Away hopped into the canoe and picked up his paddle, and Henri did the same. They maneuvered the vessel out of the swamp and back into the lake with the moonlight glimmering off its dark surface and pointed it north.

“Do you think we should return?” Henri asked.

Dances Away rested his paddle across the front of the canoe and looked over his shoulder. “Do you?”

“What we just saw, is it not proof that a battle is brewing?”

“Maybe. Or maybe not. But not now.”

“How can you be certain?”

“You heard them. They will gather information and take it back to their chief.” Dances Away shrugged. “It will be nearing winter then. No fight will happen before the trees leaf out again.”

No army wanted to fight during winter when food supplies were hard to come by.

“Then we could be home before anything happens,” Henri said.

“If anything happens.” Dances Away picked up his paddle and started the canoe forward again. “We will be rich with furs if that time comes. And Woman of the Waves will be married to someone else.”

He’d forgotten his friend was running away from a woman.

Henri hoped they were right about a possible war. He felt better about leaving Baptiste behind. A little bit, at least.

paperback ISBN: 979-8-9866966-9-0 – ebook ISBN: 979-8-9866966-8-3

Return to https://peggthomas.com/