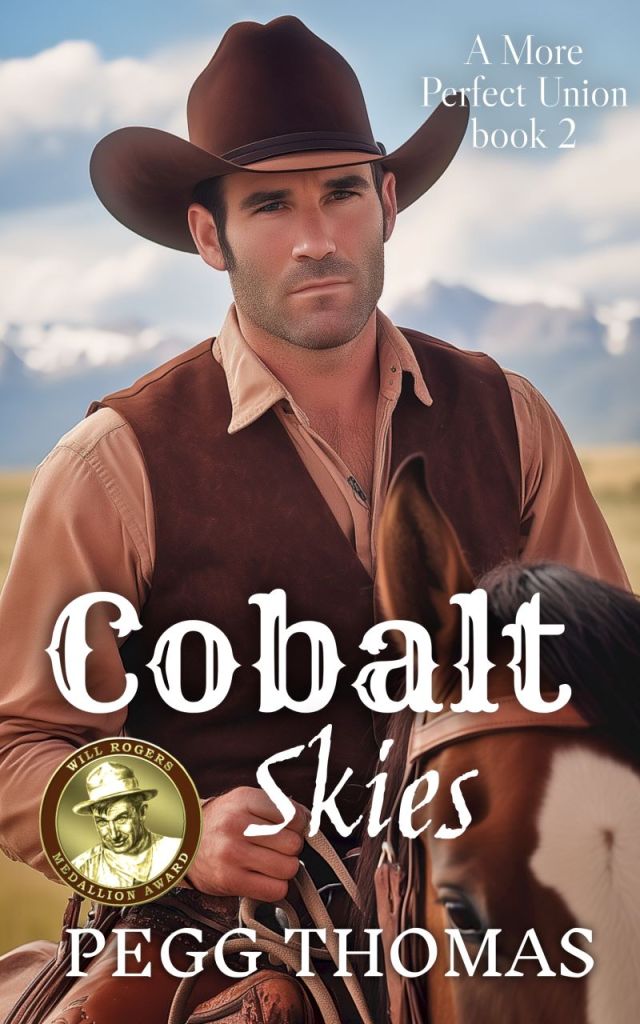

A More Perfect Union – Book 2

Winner of the 2024 Will Rogers Bronze Medallion Award

Is another clash of North and South inevitable?

Samuel Hickman had always dreamed of fighting for his country, but the realities of war had left him emotionally scarred and reclusive. Despite his best efforts to avoid people and their entanglements, fate had other plans for him.

With nothing left for her in the South, Susannah Piper sets her sights on Oregon, determined to leave behind the pain and prejudices of the past. But when she stumbles upon Hick’s camp one dark night, she finds herself drawn to the brooding soldier.

Susannah’s arrival throws Hick’s carefully crafted plans into disarray. He may be heading to Wyoming, but she refuses to be left behind. The clash of their opposing backgrounds and beliefs may spark a different kind of war between them.

Don’t miss this heart-wrenching journey through a divided America.

Tropes: Enemies to Lovers – Forced Proximity – Slow-Burn Romance – Wounded Hero – Strong but Vulnerable Heroine – Protector Romance

Chapter 1

April 1867—near Kansas City, Missouri

It would take more than an ornery bronc to stop Sam Hickman, but even he had to admit one of them could slow him down. And it had. Breath hissed between his teeth as he rubbed horse liniment into his aching hip. It was just aching, not broken, so he wouldn’t be slowed down for long. A week or two. He winced when he rubbed directly on the bruise. Maybe three.

“Hello!”

Hick pulled up his britches with one hand and grabbed his Colt .45 off the top of his saddle with the other.

“You in there, Hick?”

Recognizing the voice, he relaxed and put the pistol back. “Come on in,” he said as he secured his britches.

Big Bill Marlin opened the door of the empty stall where Hick bunked. As befitted his name, the owner of the Bar Arrow Ranch filled the opening. There weren’t many men Hick had to look up to, but Big Bill was one.

“Heard you took a bad fall.” The boss sniffed, his nose wrinkling at the pungent odor lingering in the stall. “Guess I heard rightly.”

“You did.”

“Do you want me to send for Doc Alderman?”

“Nope. I’ll be fine in a few days.”

Big Bill scratched his chin above the handkerchief tied around his throat. “I hate to say it, but I ain’t got a few days.”

Hick figured that was why the man had come. He had a contract with the army to supply horses—broke well enough for the cavalry to ride—and the pickup date was almost on top of them. A trio of ice storms had gotten them behind schedule.

“You’re one of the best I’ve ever seen.” The big man reached into his coat and drew out a wad of bills—a thin wad—and handed them to Hick. “Here’s what I owe you with a little extra to see you through until your next job.”

Not exactly fired, but a kick to Hick’s pride all the same. He took the money and stuffed it into his shirt pocket. “Much obliged.”

“Stay as long as you want. You’re welcome at the bunkhouse for meals, too, same as always.”

“I’ll move on in the morning.”

Big Bill shook his head. “Have it your way. Good luck to you.” He touched the front of his hat and left.

The man had tried to move Hick into the bunkhouse a couple of times, not understanding his need to be alone. And Hick couldn’t explain it. At least, he didn’t want to. He felt most at peace in the stall next to Trooper, his horse. Most of the hands thought him unsociable. That was fine. It kept them out of his way.

Hick had spent four long years living cheek by jowl with other men.

His fingers moved to massage the old scar on his temple. He jerked them away when he realized it. Bad habit, that. The war was over, his wounds healed, and his life was his own again, to live as he pleased.

Responsible only for himself.

***

She’d never shot a man before, and Susannah Piper wasn’t eager to pull the trigger on the heavy Colt Dragoon she clenched in both hands. But if one of those men rushed the soddy, she just might.

The squat soddy—little more than a cave in the dirt—meant nothing to her. Not with Asel gone. No, it hadn’t meant anything to her even when Asel shared it. It had been a wintering place, nothing more. A much-needed stop on the journey to Oregon. The journey to their new life in a new land away from people who hated them for who they were.

Or more to the point, for who she was.

“Mrs. Piper!” The shout came from behind the soddy barn, where Peaches was stabled. “It’s time you moved on, Mrs. Piper. Missouri has changed. We don’t want your kind here.”

Her kind.

Those men—at least three had ridden onto the property—had no idea who Susannah Mary Jessup Piper was. All they heard was her Southern accent, her thick Georgia drawl. And from that, they assumed she was a slaver and a traitorous rebel and probably a harlot to boot.

She was none of those things.

But she held the cocked pistol steady as she called out, “Get off my place. Leave me be.”

“Ma’am, your husband said you’d move on come spring. He’s gone, but spring is here. Time you honored his words.”

Susannah and Asel had arrived in the fall and taken residence in one of the many abandoned, dilapidated homesteads in Jackson County. Back in 1863, after fierce fighting between Quantrill’s Raiders and the Union Army, Brigadier General Thomas Ewing had issued Order Number Eleven, which exiled everyone in Bates, Jackson, Cass, and Vernon Counties from their homes. Susannah and Asel had chosen one of the deserted homesteads to winter in.

Susannah had every intention of moving on. Every intention of fulfilling Asel’s dream to reach Oregon. She’d sold most of their belongings—including the wagon and team of horses—anything that couldn’t be strapped to her mule or worn on her person. The coins were sewn into the lining of her oldest petticoat. But she planned to leave on her terms, not at her neighbors’ demands.

She’d had enough of being treated like the enemy.

The war was over—had been for two long years—but she and Asel hadn’t been able to get past it. He with his Union-blue britches and her with her Southern accent, they hadn’t found a place that would accept them for who they were and not for where they’d come from. Asel had been sure Oregon would be that place.

She was left to find her way there by herself.

“Leave me be,” she called, thankful that her voice was strong and smooth, not as weak and jittery as her belly.

“We’ll ride off, Mrs. Piper, but we’ll be back tomorrow, and the tomorrow after that, and the tomorrow after that until we’ve flushed you out. There’s no place here for the likes of you.”

Hoofbeats were followed by dust visible through the soddy’s only window. Had they all left? Or was it a trap to draw her out?

Susannah glanced at her sack, saddlebag, leather satchel, and the makeshift saddle she’d cobbled together from an old pack saddle, a buffalo hide, and some rope. It wasn’t pretty, but it would hold her and all her worldly possessions. She’d wait for an hour or so to make sure the men—her so-called neighbors—had gone, then she’d ready Peaches and ride out.

She should be able to make Kansas City by evening. She’d camp somewhere near there and enter the city in the morning. It shouldn’t be too hard to escape notice until then.

She’d gotten very good at traveling unseen. Sneaking around wasn’t a skill Susannah had been born with, or one she’d learned as a young girl growing up in Blackshear. No, she hadn’t learned it until she’d helped Asel escape. So in a way, she could blame her newfound skill on William Tecumseh Sherman. If he hadn’t been on the march, the Confederacy wouldn’t have needed to move prisoners out of Andersonville and stow them in temporary prisons like the one near her home. Prisons without walls or fences. Prisons men could escape from. Union soldiers.

Like Asel.

No, traveling unseen wasn’t a skill she’d learned as a youngster. But it was a skill she needed as a grown woman. Again.

***

Of all the bad luck. Hick let go of Trooper’s front hoof and then picked up the rear one. At least the shoe on that one wasn’t broken. But the front shoe was. He checked the other two, both badly worn but in one piece.

Hick mentally kicked himself for not asking the farrier at the Bar Arrow to put new shoes on Trooper. He would have, and Big Bill wouldn’t have charged him for it. But his stubborn pride had gotten in the way. And Trooper was paying the price.

“Sorry, boy.” He scratched the war horse’s rump above the tail. “Should have thought more about you and less about me back at the ranch.”

The horse turned his mostly white face to Hick, one blue eye and one brown eye blinking at him. They’d covered a lot of miles, ridden across too many battlefields, and faced death together more than once. The horse didn’t deserve to go lame because Hick had been neglectful. He’d been sure the shoes would last as far as Kansas City.

He’d been wrong.

He led the horse to a grassy spot near the trees that grew along the river. It’d be a good place to camp. He let Trooper drink his fill, then stripped off his tack and gear. After fishing out his hatchet, he worked the broken shoe off the hoof, then hobbled the old horse so he wouldn’t range too far.

The river was narrow there and deep, the water refreshingly clear. Hick filled both his canteens. Standing and straightening, he winced at the pain in his hip. Another night of rest would do it some good. But walking into town tomorrow?

Hick was a horseman, a cavalryman. Walking didn’t set well with his disposition. But it was his own fault. He wouldn’t compromise Trooper’s feet for anything. Even his own. And his boots weren’t in much better shape than the old horse’s shoes.

With his coffeepot settled near the fire he’d built and a few thick slices of bacon sizzling in the pan, Hick relaxed against his saddle and watched the evening gather around him. The wind blew softly for a change, and the croaking of frogs and humming of insects grew louder as the darkness thickened. He may have dozed, but the scent of scorching bacon and boiling coffee roused him in a hurry. After setting the coffeepot aside to let the grounds settle, he slapped the bacon on his plate and leaned back against his saddle again.

His bum hip was going to force him to slow down, and slowing down left him time to think about where he was going. Since the war, he’d been drifting, working on this farm or that, making his way west until he reached the ranches. He knew horses, and he could make a good living breaking new stock, but at some point, he needed to think beyond that.

Thinking about the future was one of the hardest things for him to do when so many men had died in the war. Men who had no future to think on.

Why had Hick survived? Why him and not Denny? The pain struck as it always did when he thought of his brother. He rubbed the center of his chest. It should be Denny figuring out what he wanted to do with his life. He could picture his brother on a farm near their folks’ place in Ohio. He’d have a pretty little wife and a trio of children by now. His future should have been all that and more.

But he’d followed Hick into the war.

He’d followed because Hick had talked of little else but honor and glory and service to the country. There may have been service to the country, but honor and glory he’d seen none of. War had been nothing like he’d imagined beneath the spreading oak trees on Pa’s farm.

It had been…brutal.

***

Susannah dropped a handful of early wildflowers onto the mound at her feet. A crude cross made of sticks and rope held up by a circle of stones marked one end of the grave. Green sprouts pushed through the stark brown earth. New life taking over the old.

“‘Bye, Asel. I wish it hadn’t ended like this.”

There were no tears. She’d shed enough of them weeks before. Theirs hadn’t been a conventional marriage. It had been born of need, not love. But she had grown to love the gentle man she’d worked so hard and risked so much to save. Twice.

If only she’d been successful the second time.

But the season for those thoughts was long past. She must move forward. She must leave Missouri and its growing hatred of anything Southern behind. Oregon was her future. Asel had been sure they could rebuild their lives there. Maybe even start the family they’d both wanted, although she’d not conceived. He’d said that any folks willing to work hard could make a place for themselves in Oregon, which had never been part of the war.

“I don’t know how we’ll make it, Peaches.”

The mule twitched an ear but didn’t bother to raise her head.

“Oregon is a long, long way from here.”

She glanced at the mule’s overgrown, cracked hooves. Those must be addressed before they reached St. Joseph. No wagon master would take her if it looked like she’d neglected her animal. Asel would have taken care of those hooves, but Susannah lacked the knowledge. She’d have to find a farrier in Kansas City.

Susannah saddled the molly and tied on her bedroll, saddlebag, sack, and satchel, double-checking that everything was secure. There was no graceful way to mount, but she got her foot into the loop of rope that would serve as her stirrup and pulled herself up, hooking her knee over one horn of the converted pack saddle. It lacked any comfort of a sidesaddle, but the alternative was to ride astride like a man. On her makeshift contraption, that wouldn’t be any more comfortable.

She turned Peaches toward the river and urged her on without looking back. Looking back hadn’t done her any good in Georgia or Kentucky and it wouldn’t do her any good in Missouri either.

Once she reached the river, she’d have some cover from the willows and scrubby trees that grew along its banks, enough to shield her from the boat traffic if she was careful. Enough to hide in if others were traveling by horse or wagon or even on foot.

She tapped the leather holster she’d fashioned for the front of the saddle, the hard length of the Colt Dragoon reassuring her that she could protect herself if she must.

How much she’d changed in two and a half years. From a doctor’s daughter, working to help the sick and injured, to a woman on her own prepared to use a gun if need be.

Susannah turned her face to the sun. It was a new day. She had a new goal. And—Lord willing—she’d be in Kansas City the next afternoon. She’d buy a few provisions and make her way north to St. Joseph, where the wagon trains formed. From then on, she’d face each day as it came and survive as best she could.

Alone.

paperback ISBN: 979-8-9850278-8-4 – ebook ISBN: 979-8-9850278-9-1

Return to https://peggthomas.com/